In February 2013, I was the sound designer for Carnegie Mellon’s production of Spring Awakening. It was the most holistic process of any show I’ve worked on, and the new German Tanztheater approach resulted in an exciting and moving finished product. The sound design presented some unique challenges in some new ways for me, so I’ll describe some of them here.

Sound Design Goals

First and Foremost

We needed to make sure that the audience could hear all of the words, that the sound design had the agility and clarity to deliver the diverse score to the audience, and that all audience members had a similar aural experience regardless of where they sat.

Conceptual

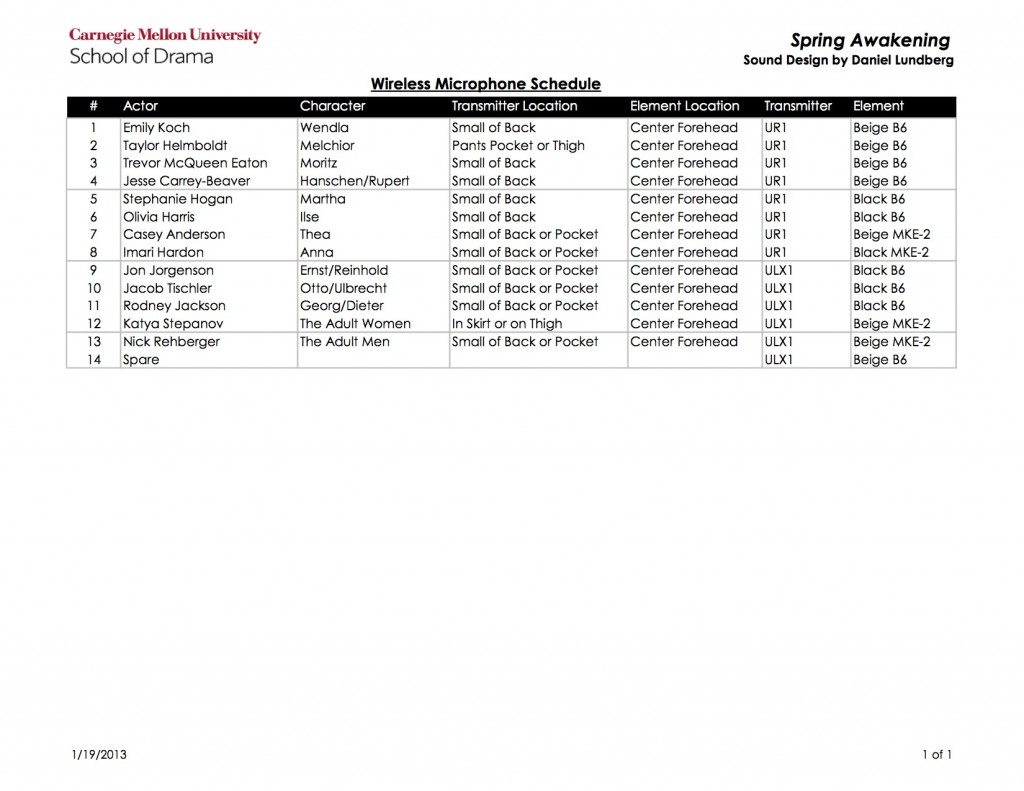

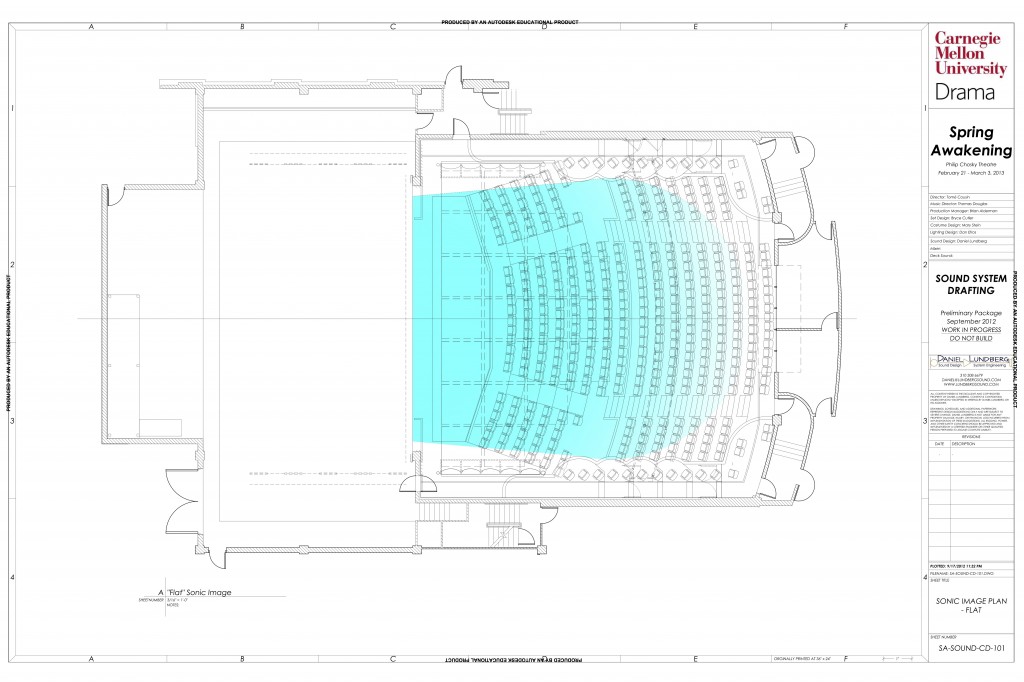

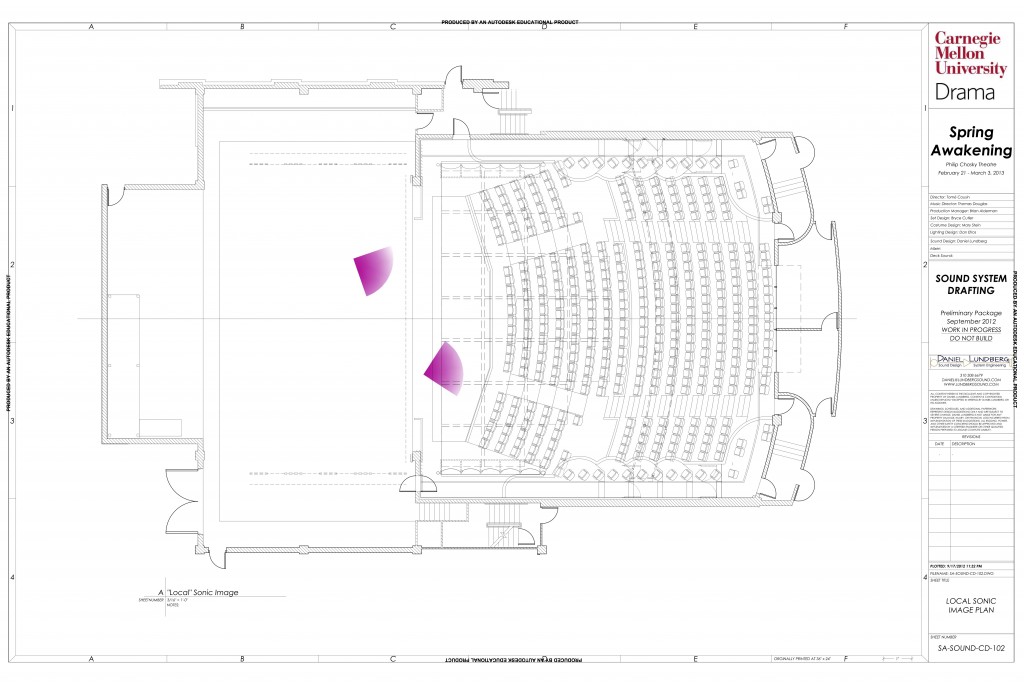

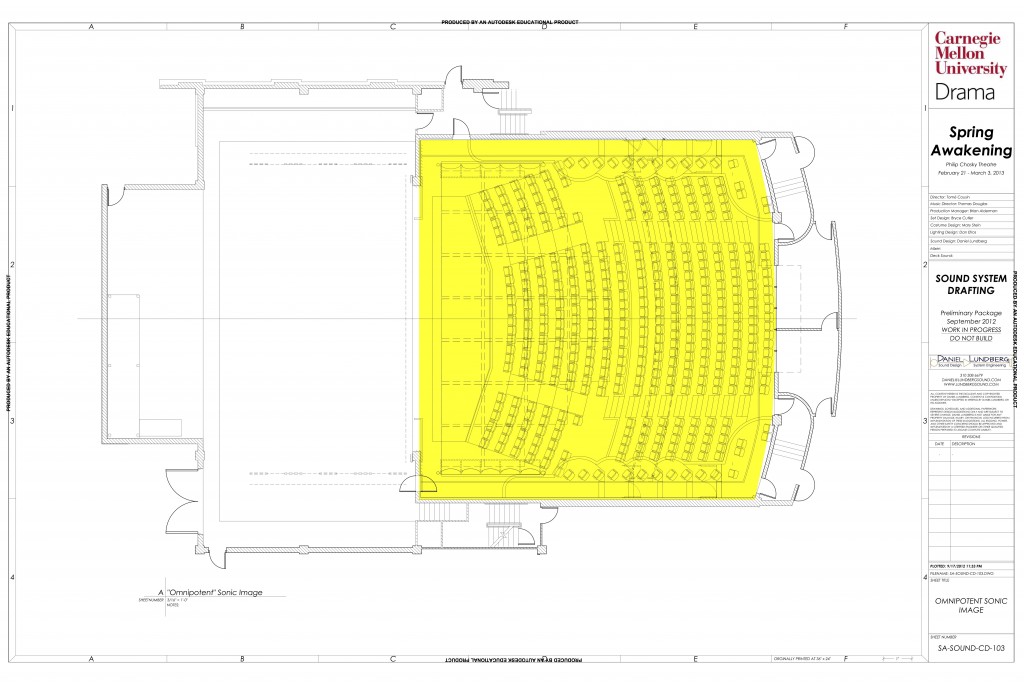

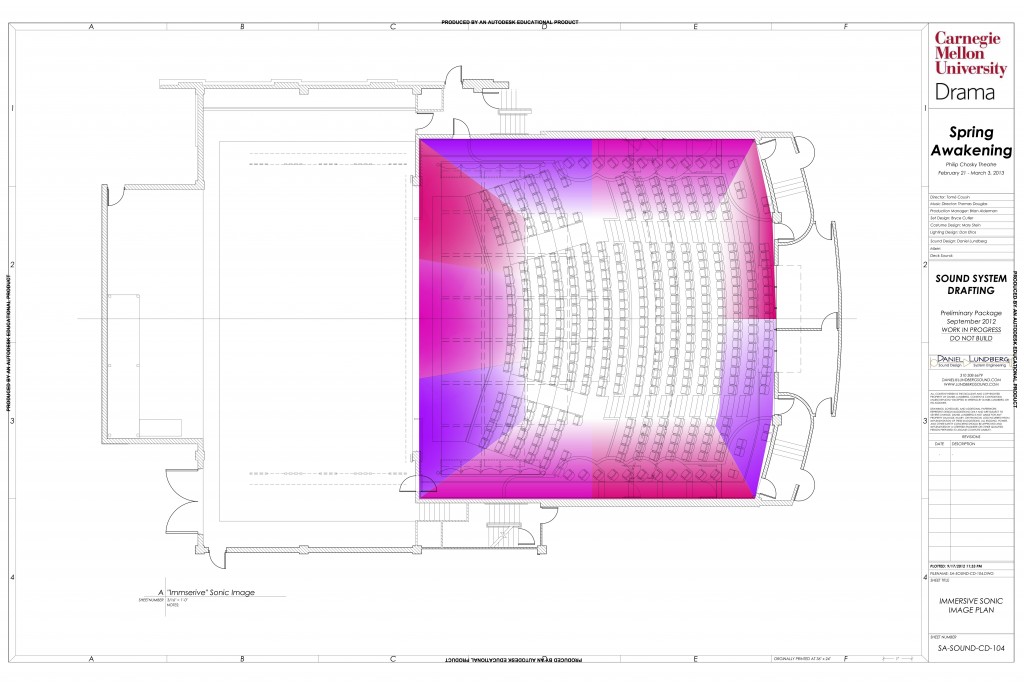

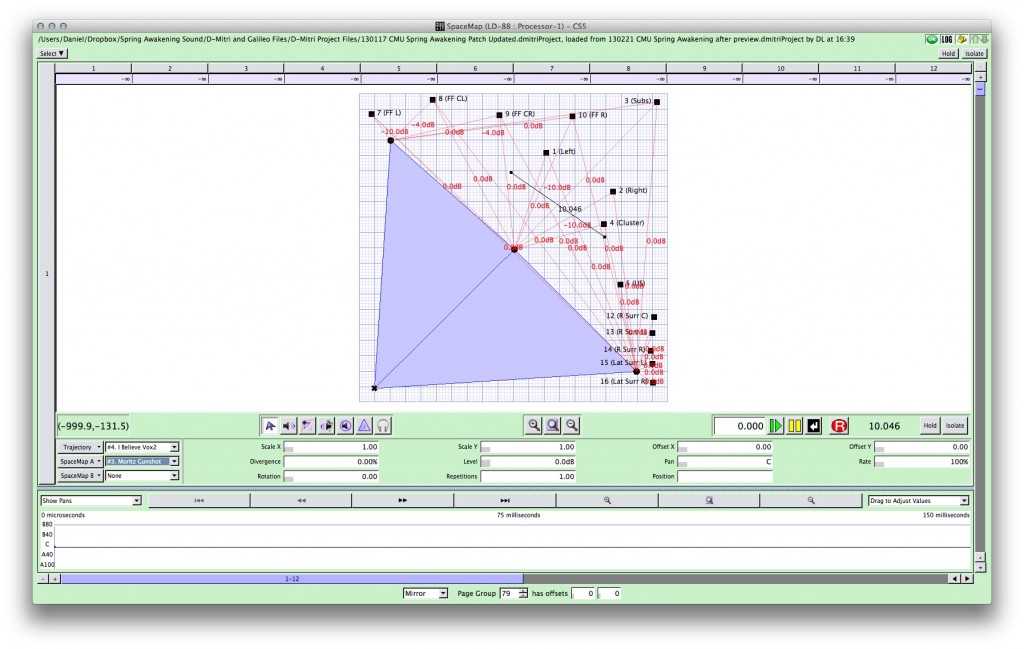

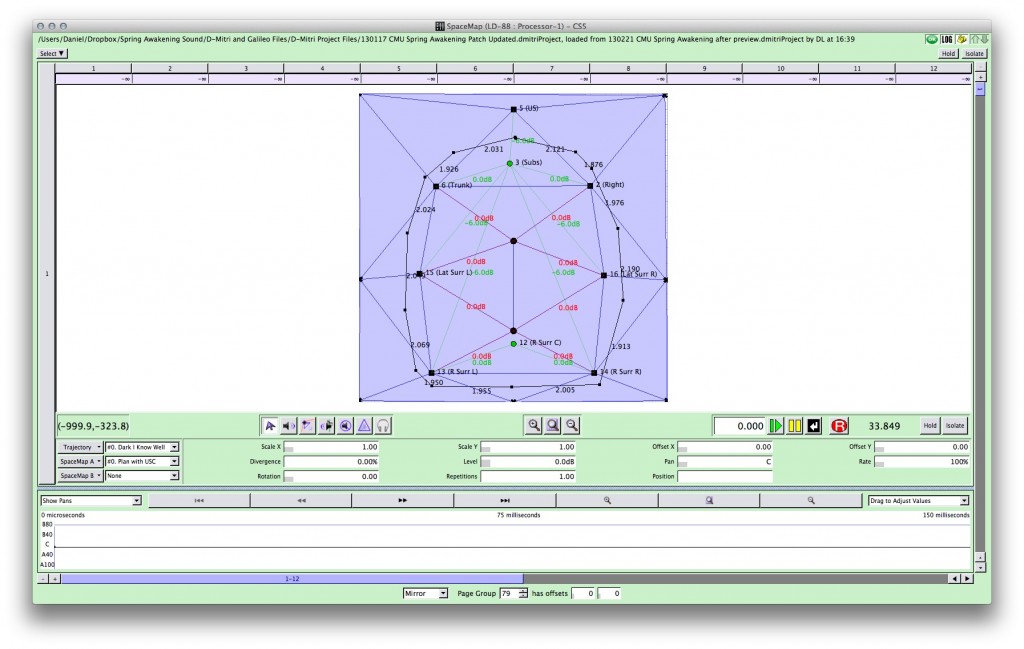

The adults have created the world in which the kids are confined, so we initially talked about using sound to put the adults on an “omnipotent pedestal.” We linked spatiality in sound with the kids’ emotional arc, going from a flat sonic image to a completely immersive band and vocal mix. I made some goofy graphical representations of how we wanted the sound to feel:

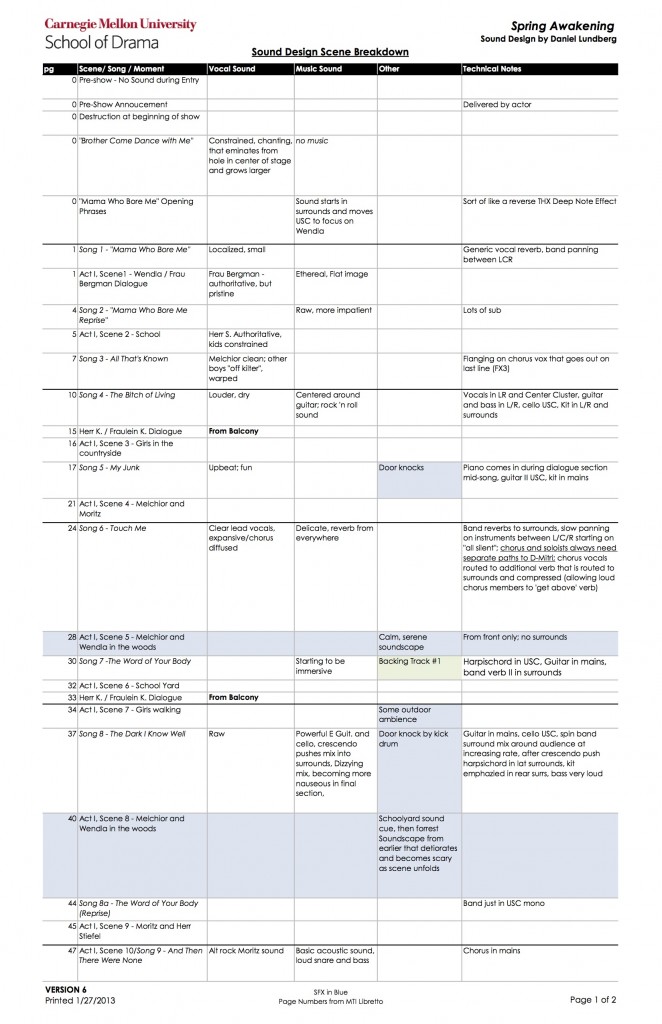

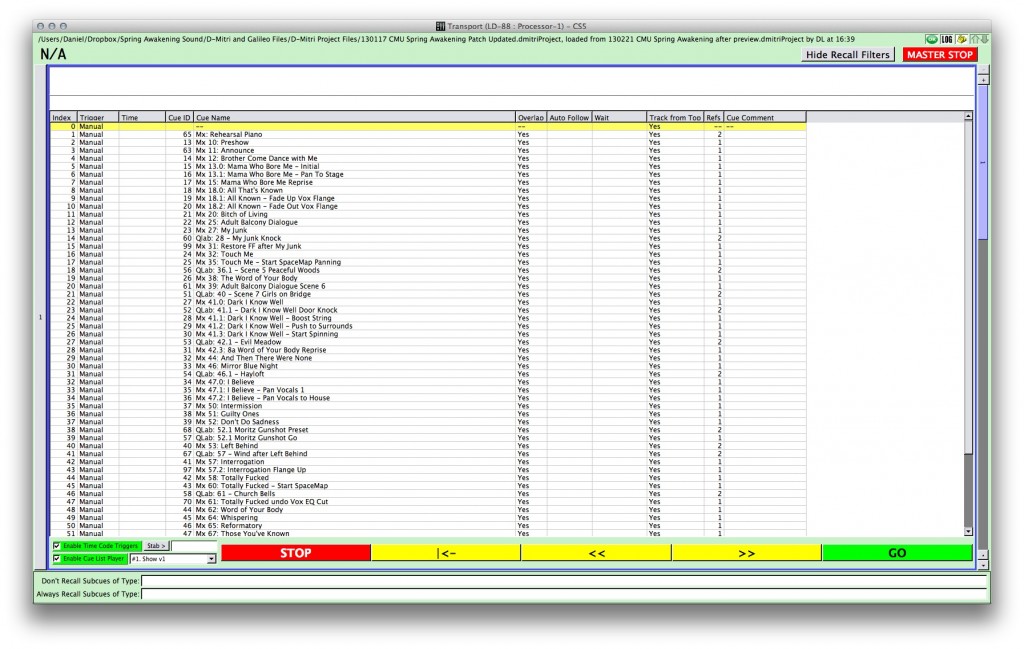

This basic idea lead to the development of a “Sound Design Scene Breakdown,” where the whole team talked through the script, decided how we wanted to tell the story in each moment, and figured out which element(s) could best do that. The Sound Design Scene Breakdown went through many iterations, beginning with how we wanted particular moments to feel, and getting more technical as we approached tech so that we could refer to it when setting base mixes.

Practical

Because of the heavy choreography throughout the show, actors could not use handheld microphones, and microphones they did wear couldn’t restrict movement or be visually obtrusive. Loudspeakers had to be mostly out of the stage picture. Actors needed to hear the band, the band needed to hear actors, there needed to be intercom, etc.

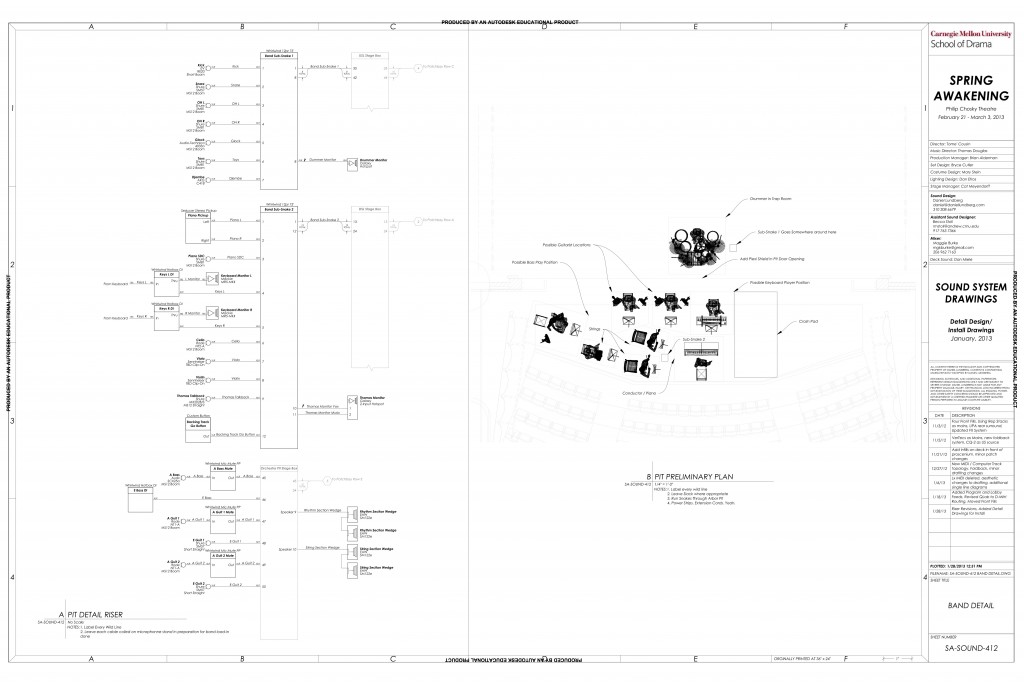

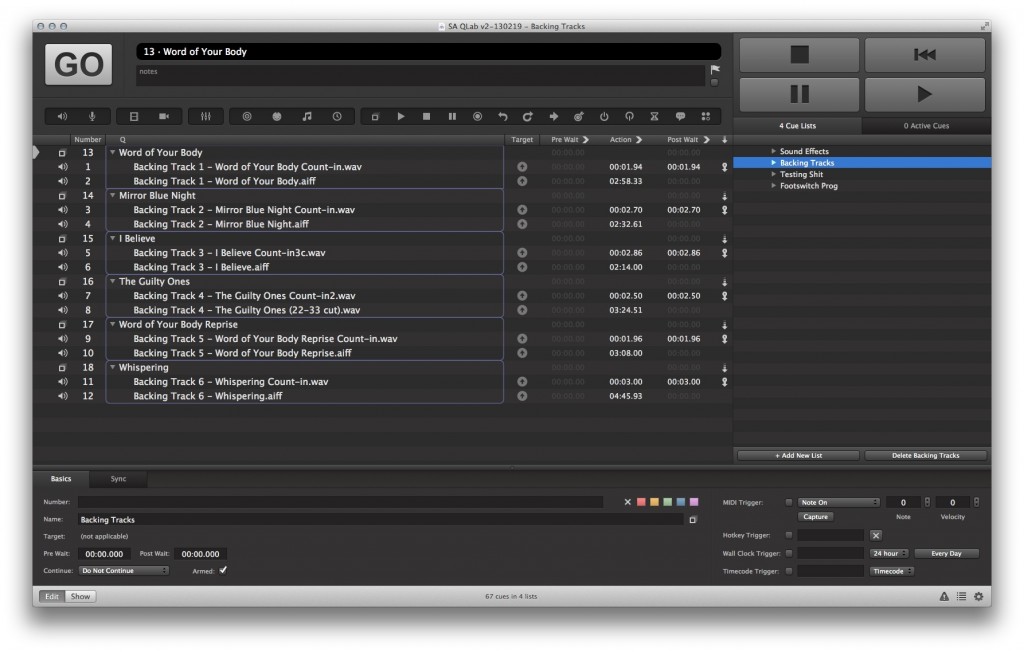

There was also the matter of backing tracks: the orchestrations from MTI came with a CD of backing tracks for some synth percussion and harpsichord music, and there is no book for these parts from which to play them live. Rather than reverse-engineer a book and call for another keyboard player / deal with another keyboard, we decided to use the tracks. In order for the band to sync with the tracks, we recorded count-ins for each that the MD would hear through headphones, and then the band would play along.

Preliminary System Design

Front End

In early September I laid out the requirements of the front end. It needed:

- Band snapshot automation – Because of the stylistic range of the music and the planned movement of pieces of the band throughout the house, we needed some form of automation on the band that would let us drastically tailor our base mix to each song.

- Band, vocal, and SFX spatial panning – Beyond having several mixes with unique use of space, we wanted the transitions between mixes to be spatially dynamic.

- Band, vocal, and SFX VCA control – Like a typical medium-to-large scale musical, this needed to be mixed line-by-line, requiring all vocal microphones for soloists and groups to be assigned to VCAs on a scene-by-scene basis, with the band and SFX having their own dedicated VCAs.

- Multitrack recording – Since we’d have three chances to hear the orchestra play the show before we played to an audience, we figured it could help to have full multitrack recording with ‘virtual soundcheck’ capabilities.

- Redundancy and facilities for non-Spring Awakening use – During Spring Awakening’s time in the venue, the venue would also be used for classes, assemblies, and miscellany so we needed to put generic stereo audio sources and single microphones through the main PA. We also wanted some degree of redundancy so that the show could go on for any single-point failure.

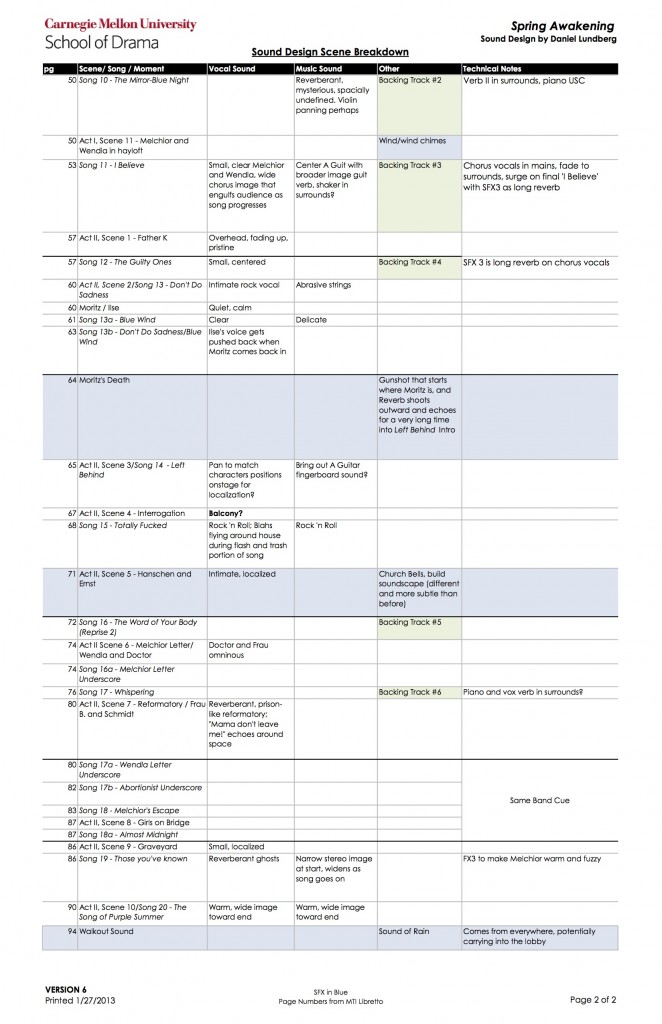

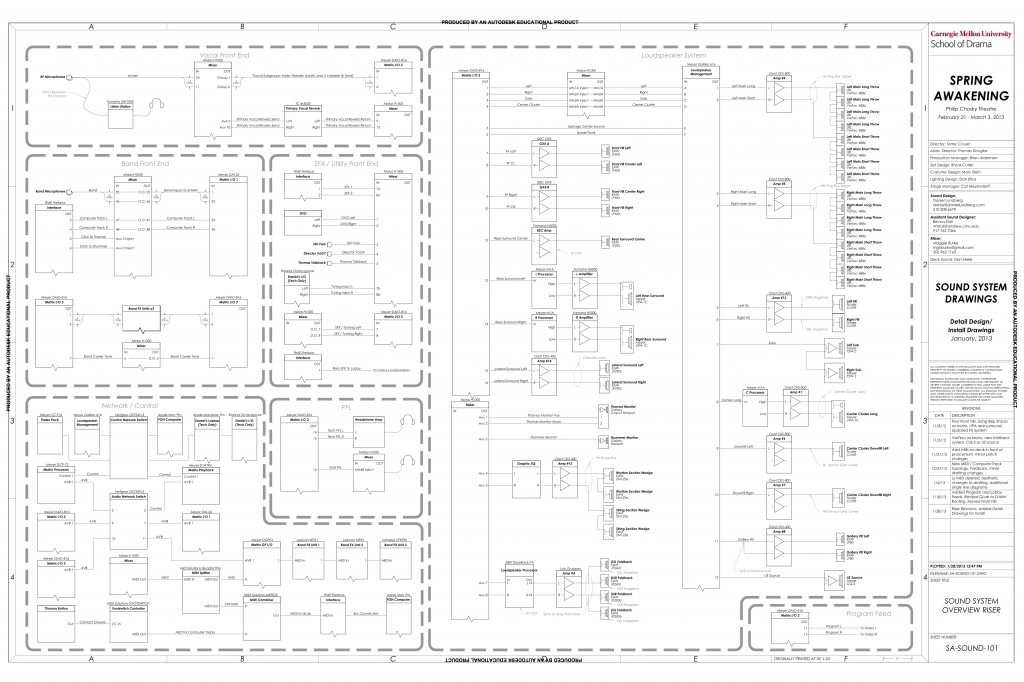

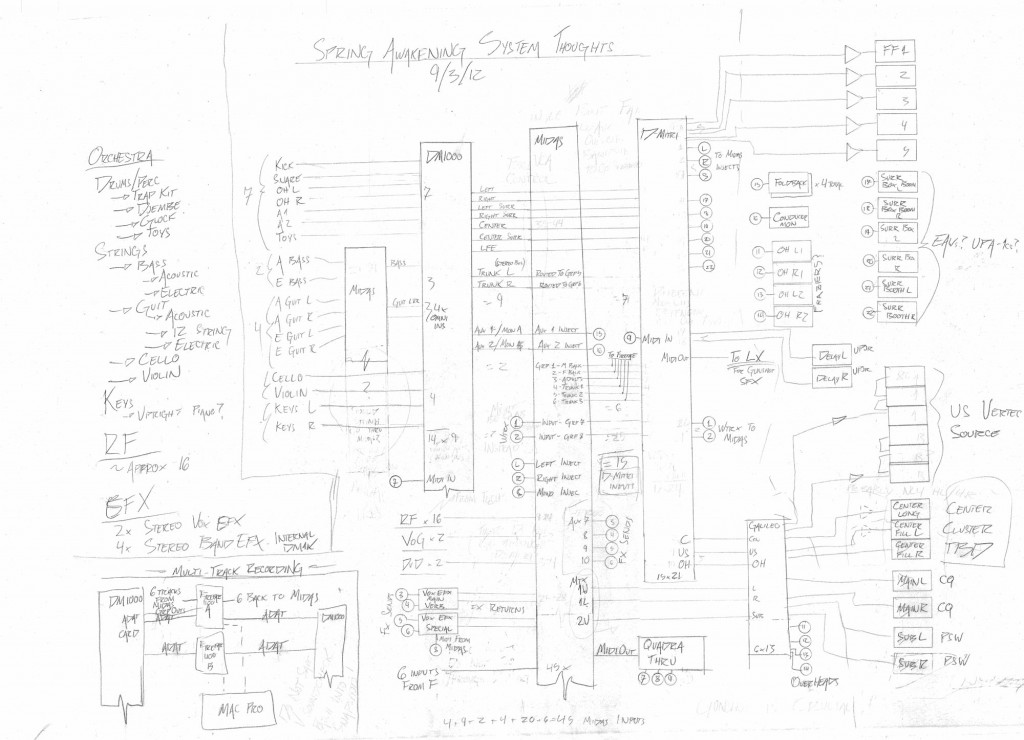

So, I started out with a rather complicated preliminary system riser:

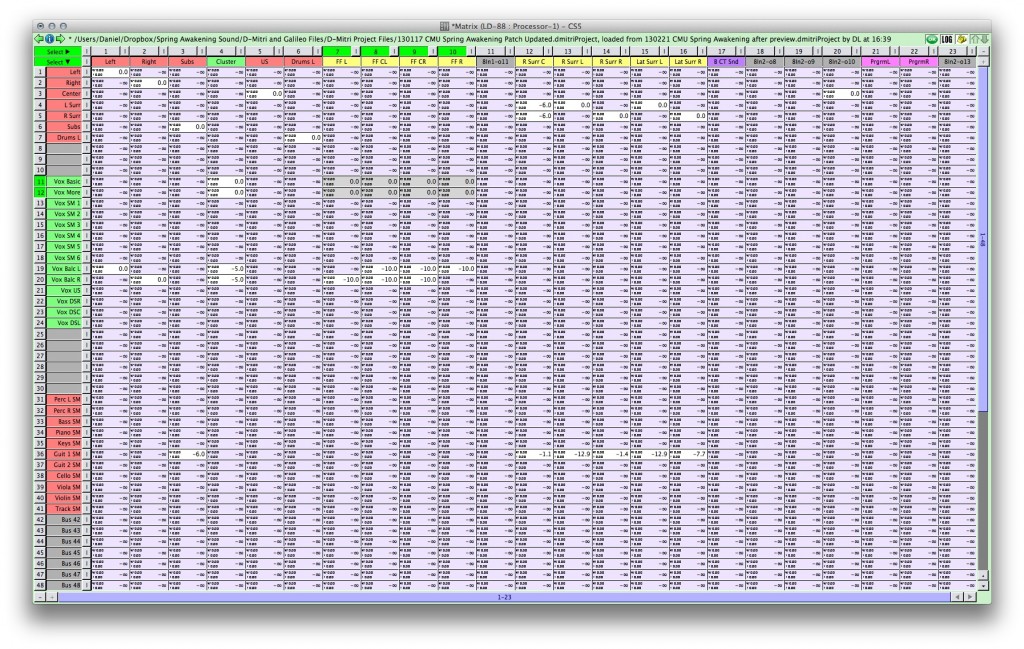

The idea here was that the DM1000 would cover most of the band mix as a submixer for the Heritage 1000 as the primary console. It would send a 6-channel quasi-5.1 mix into the Heritage for VCA control, and the post-fade direct outs of those six channels would go into our 16×32 D-Mitri system for the spatial business, along with several more channels for vocal and SFX. Playback would be via Wildtracks, but would come out of D-Mitri, go into the Heritage for VCA control, and then go back into D-Mitri. Multitrack recording would’ve been some convoluted solution with Mini-YGDAI cards and aggregate devices.

A lot of the functionality was there, but it wasn’t an elegant system design. The DM1000 would be doing the heavy lifting for the band, and the multitrack recording system was too complicated to justify its use. Plus, we didn’t have all of the necessary components.

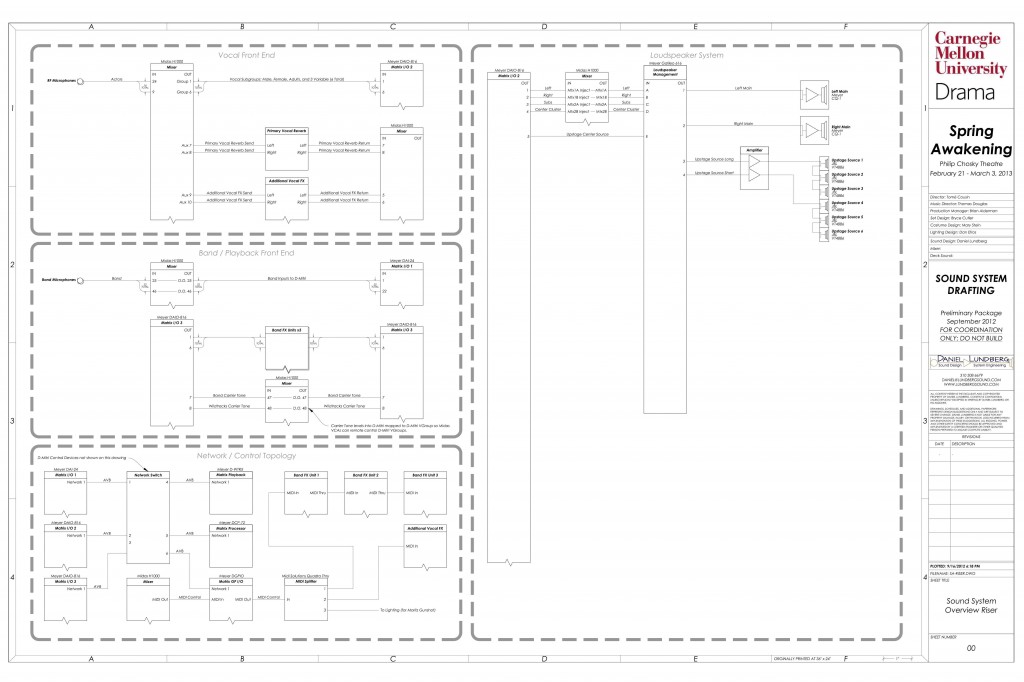

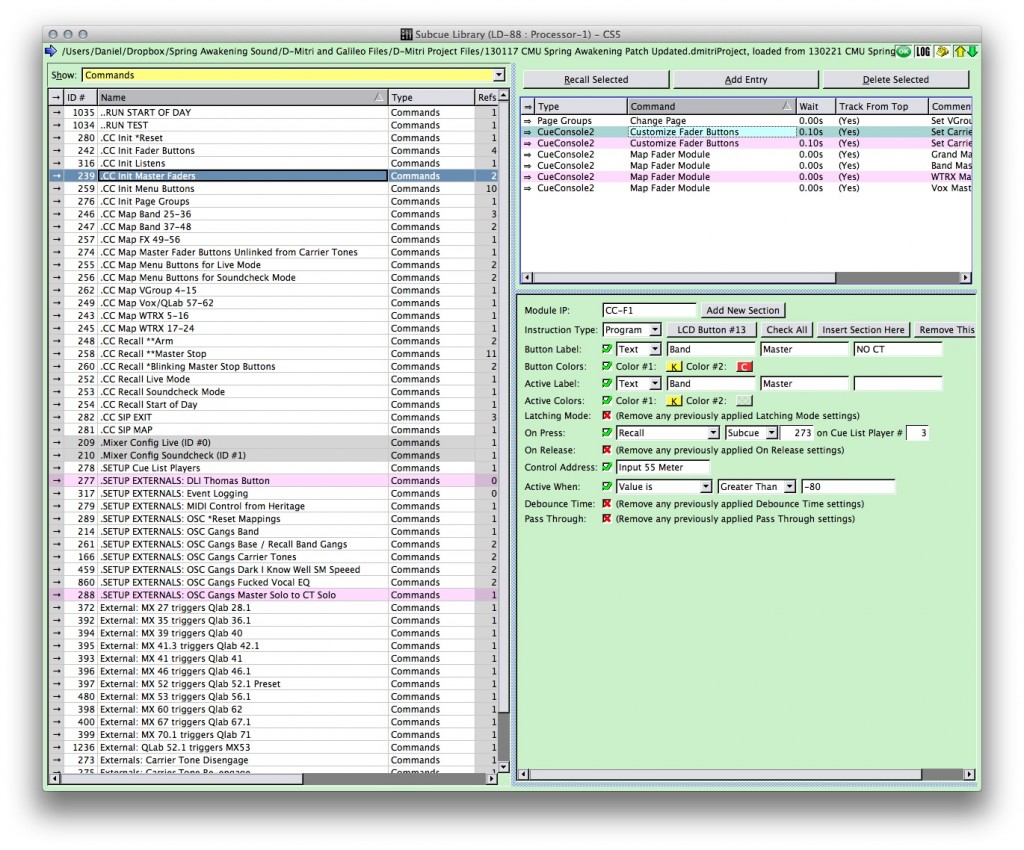

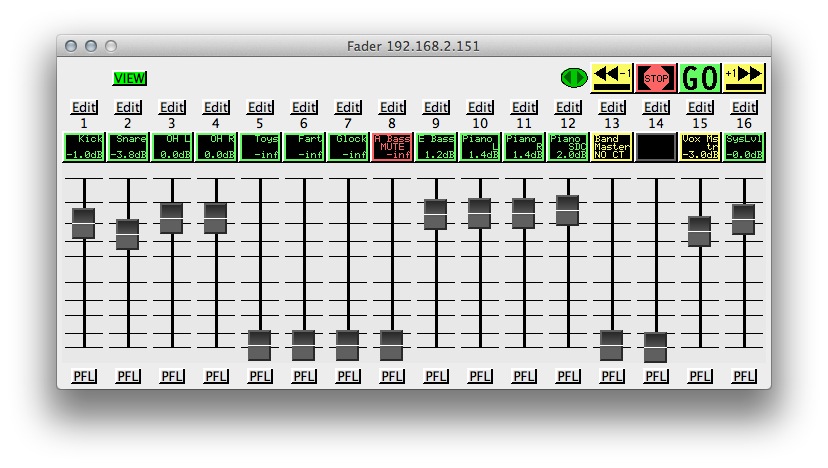

After going over it with some peers and reevaluating, I came up with a Midas front end for all band, vocal, and SFX inputs, with a D-Mitri downstream for the spatial business and the band mix automation. This would leave the operator with a “hard,” or automation-safe, control over band levels, head amps, and EQs, and would simplify multitrack recording by using Wildtracks. Vocals would be sent to D-Mitri in from six Heritage groups, i.e., we could get six separate vocal mixes depending on whose microphones we needed to control separately in any given scene. This approach had a couple problems. First, we would need 40 inputs into D-Mitri, for which we didn’t have the hardware. Second, if we were using dynamics in D-Mitri, they would be downstream of the VCA control on the Midas, altering the signals’ relationship to dyanmics thresholds. The solution for this was to create a “carrier tone:” a sinewave that came out of D-Mitri and into the Heritage for level control, and then back to the D-Mitri. The input level of the carrier tone signal in D-Mitri would be linked to the D-Mitri band master VCA, so when the carrier tone’s level was changed on the Heritage, the band master level in D-Mitri would track.

Because of D-Mitri’s central role, we wanted a way to bypass the D-Mitri in the event that something went terribly awry and the operator wasn’t able to fix it during the show, so the main outputs from the D-Mitri went back through the matrix of the Heritage and to the Galileo. This way, we could get to the main PA by sending spare/redundant subgroups to those matrix outputs. We never had to revert to this.

Playback would come from Wildtracks in D-Mitri, with a button for the music director to trigger the backing tracks.

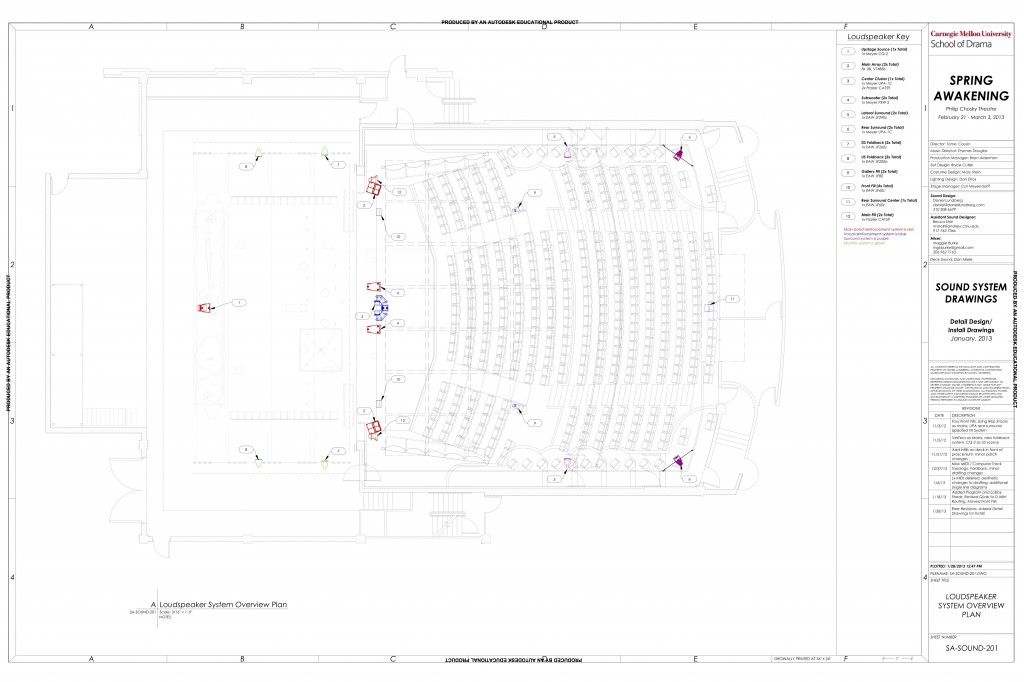

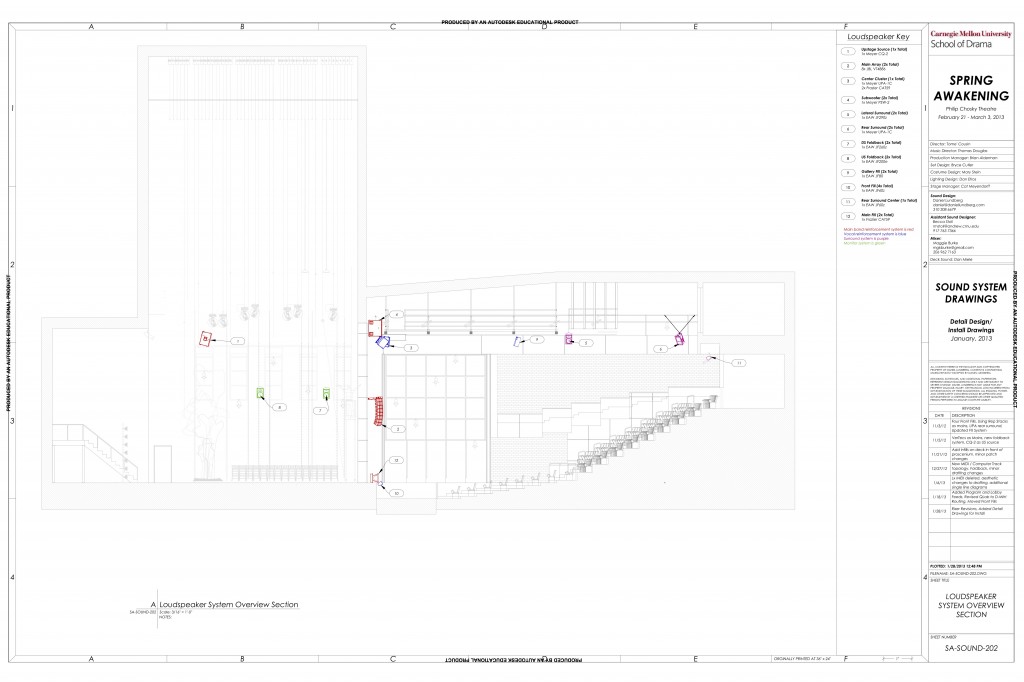

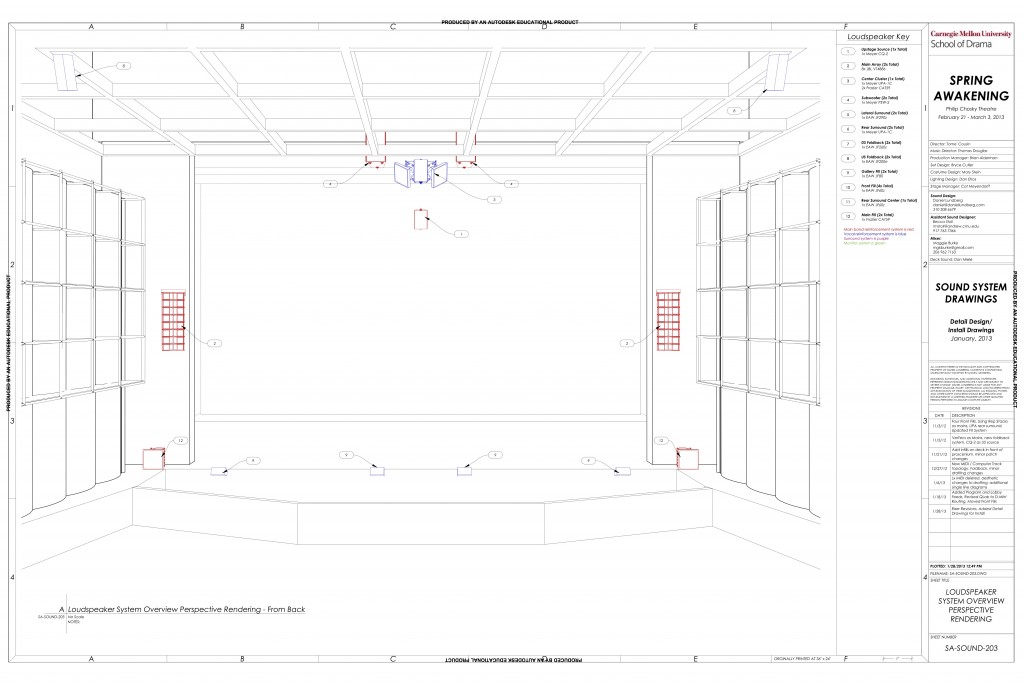

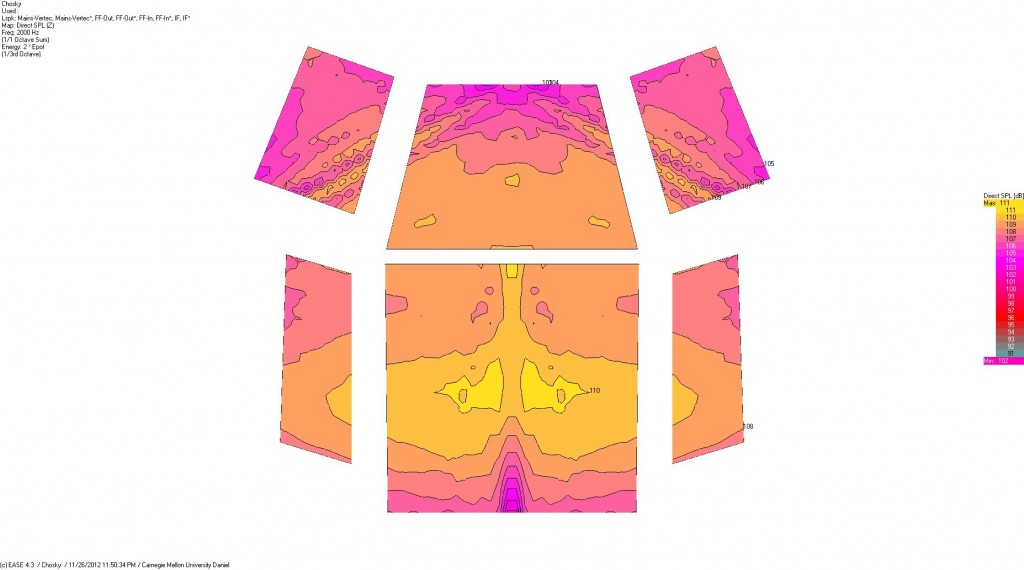

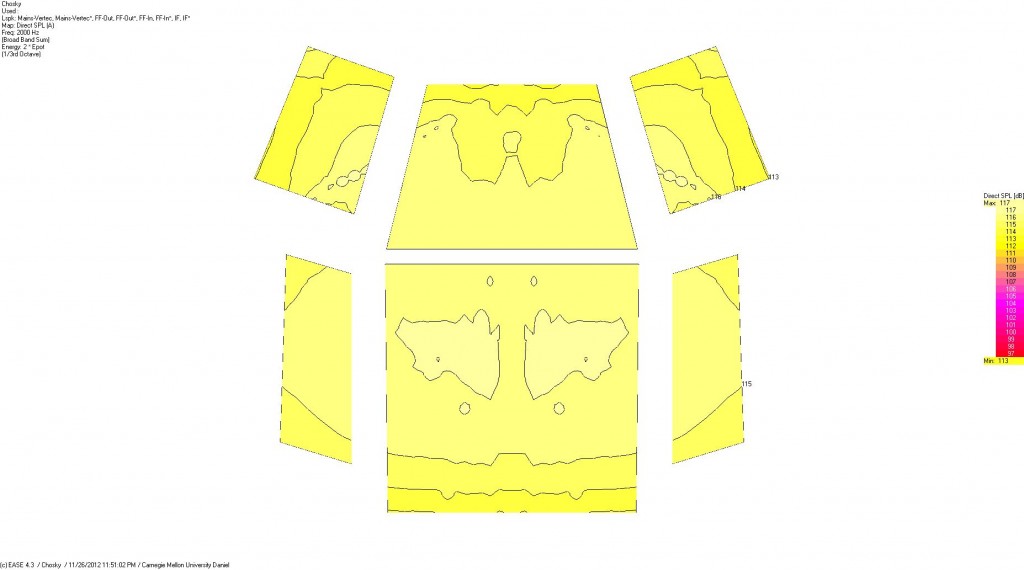

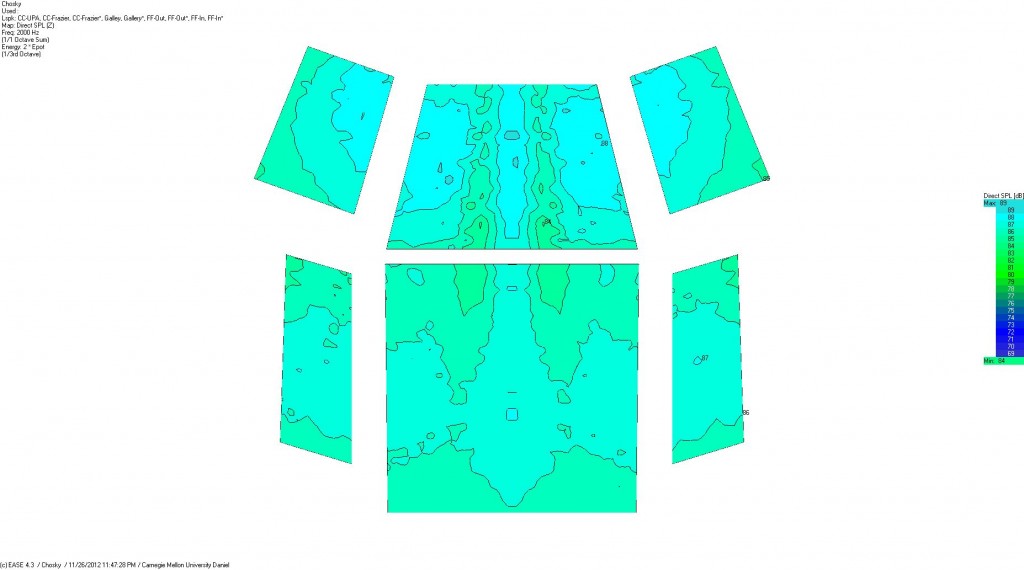

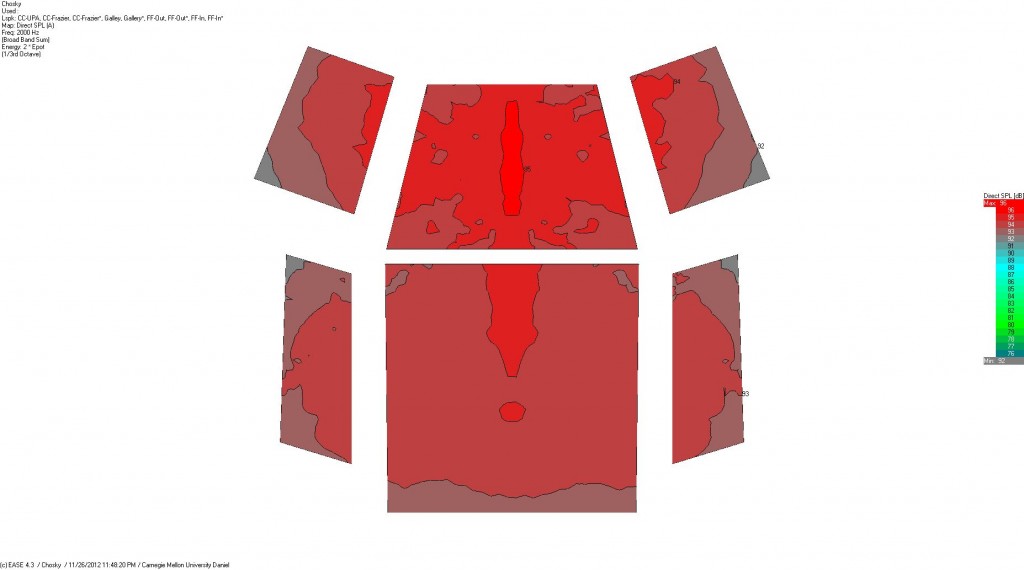

Loudspeakers

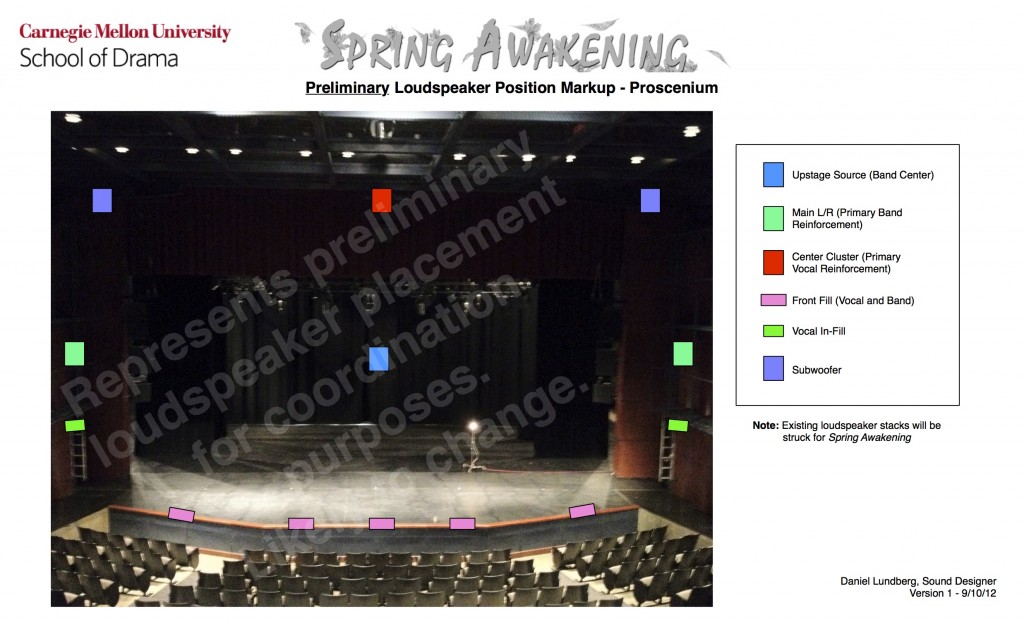

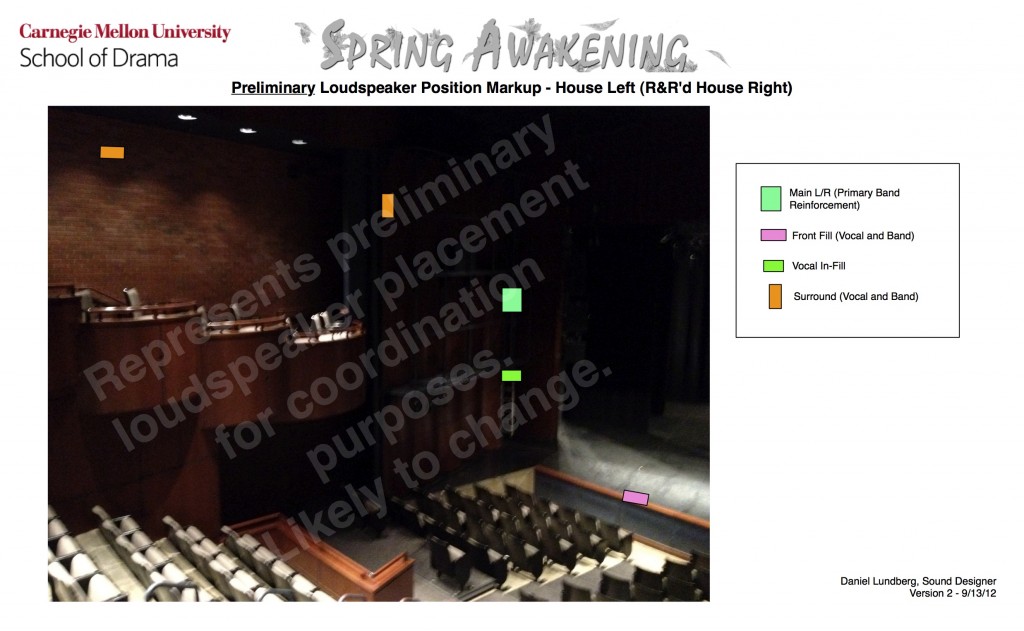

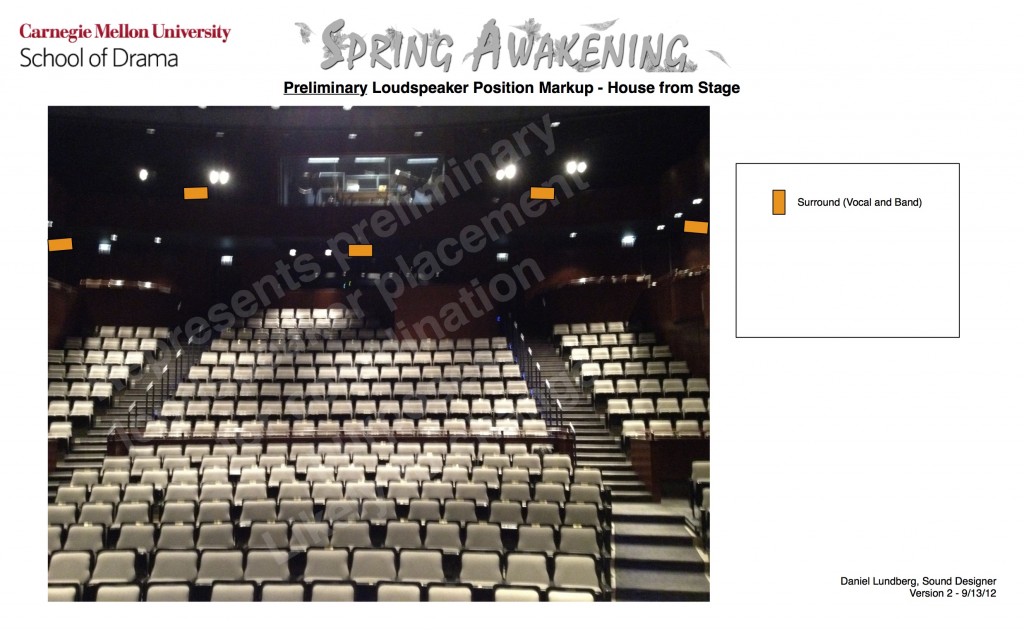

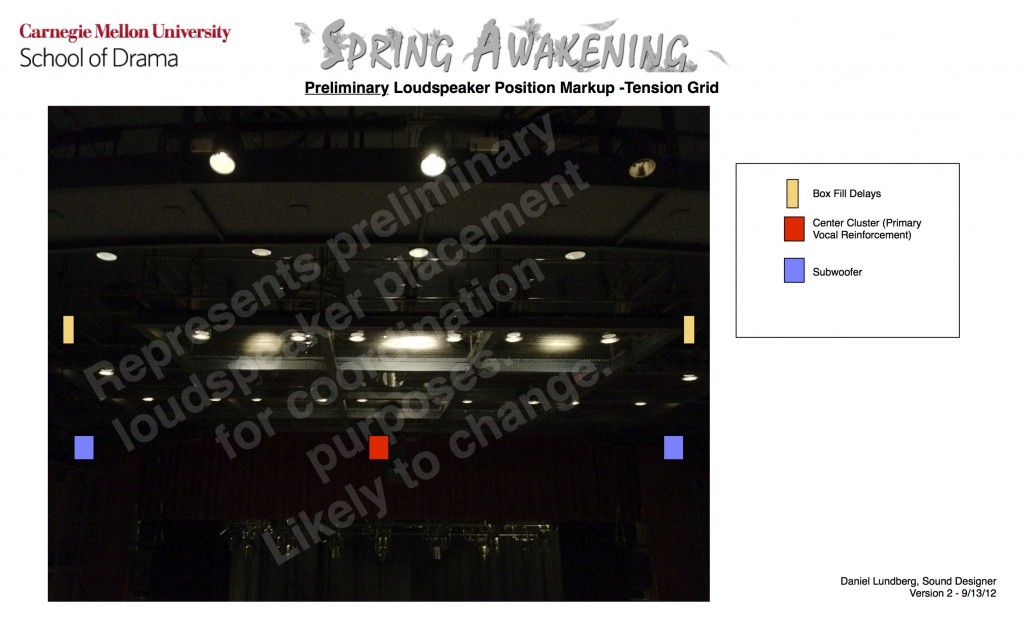

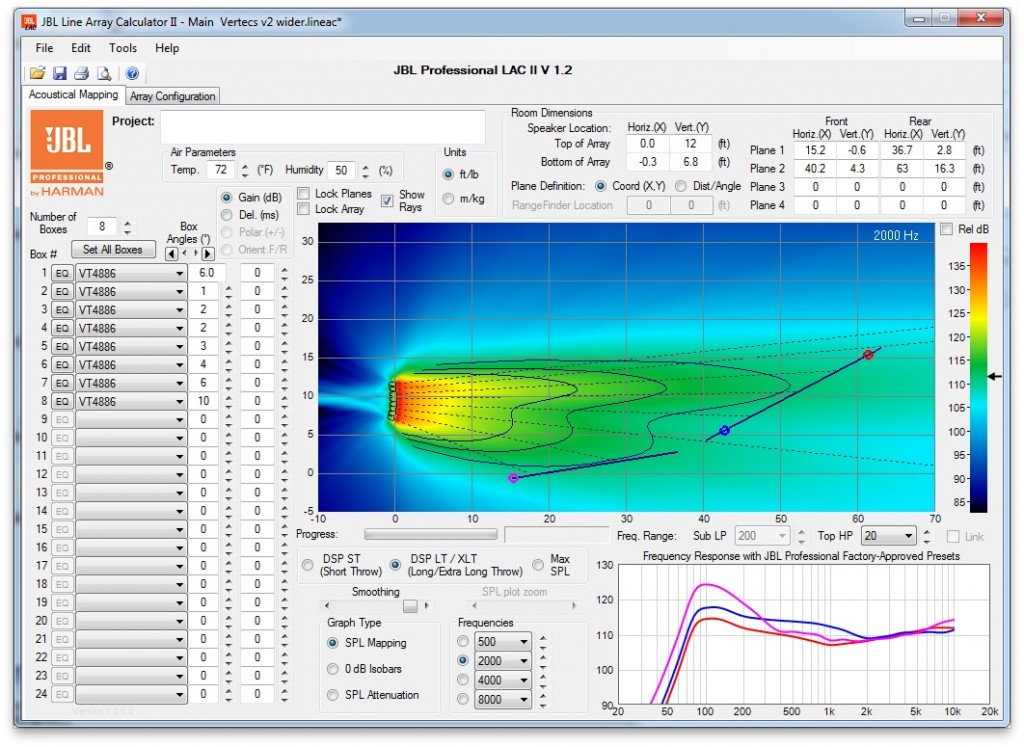

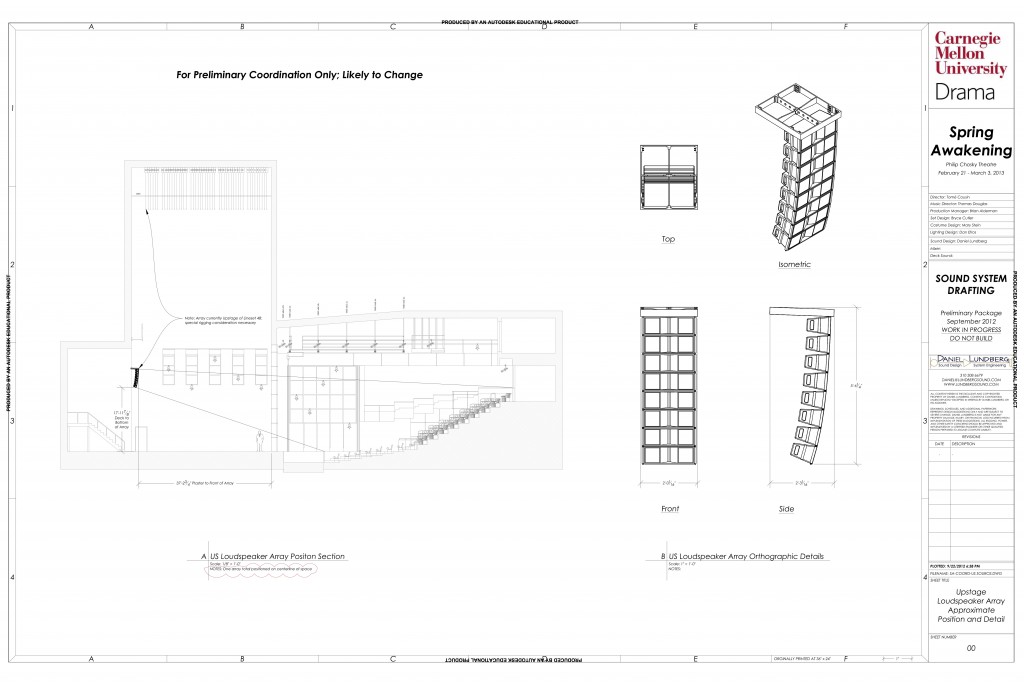

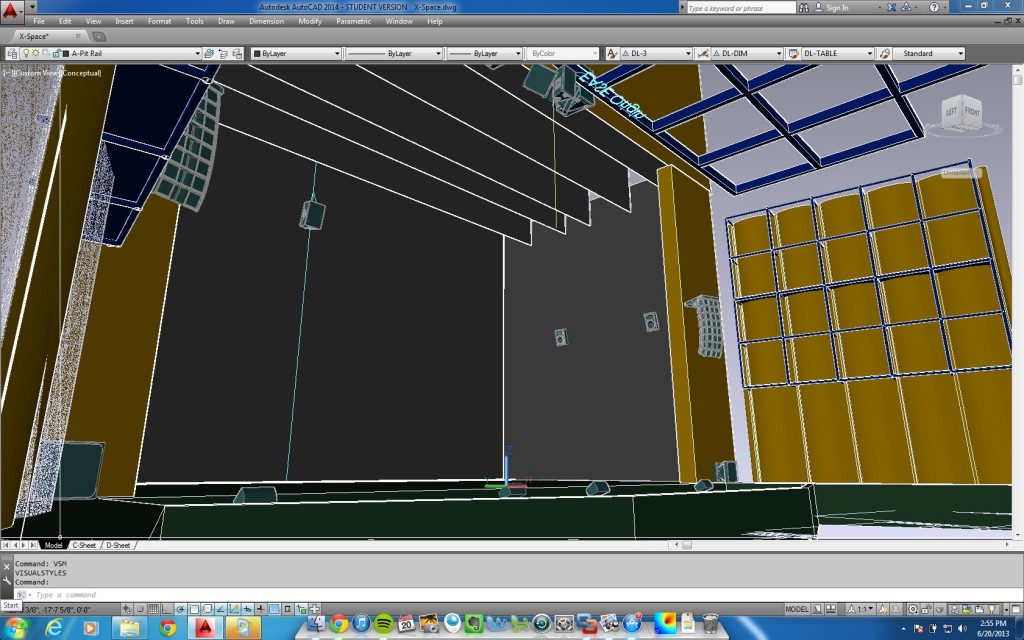

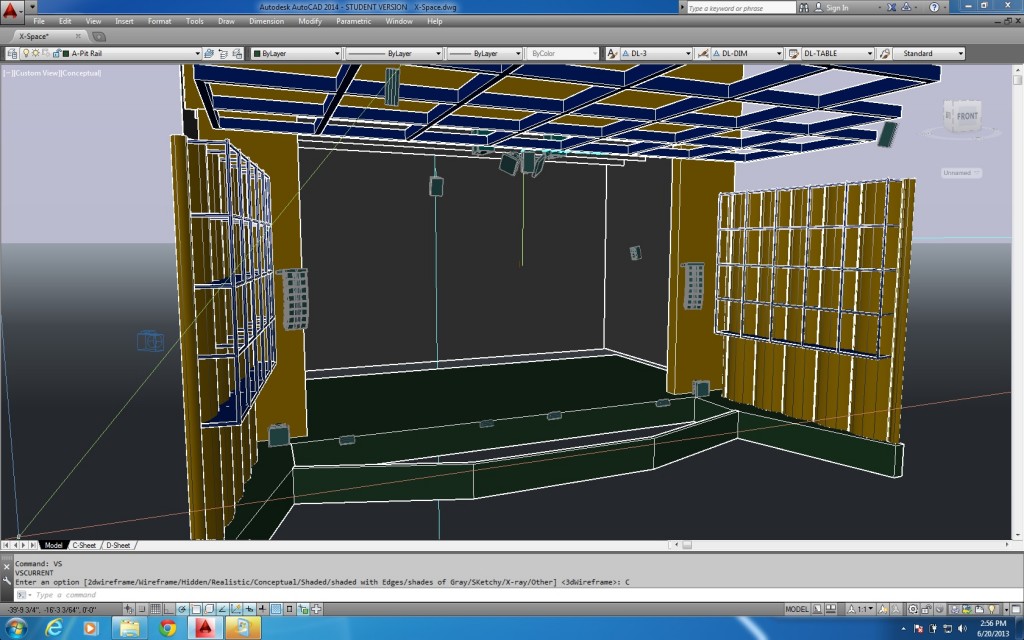

We approached this rather traditionally: a vocal system anchored by a center cluster, with edges of coverage filled in by front fill and delays; a left/right system for the band, with fill loudspeakers close to the stage and accompanying subwoofers; a surround system; and foldback for the actors. One additional component we wanted was an upstage loudspeaker for band reinforcement — because the house was too wide for audience members to get a stereo experience from the L/R system, a center source for the band would allow us to pan in/out rather than left/right, creating more separation in the mix. The center cluster wasn’t the best option for this because the azimuth angle from the audience would’ve been significantly greater. Also, the center cluster’s coverage relied on front fill, so people in the front would not get the same in/out experience because some would be inside the front fill array. The solution was to put a loudspeaker (or in the first draft, a loudspeaker array) in plain sight upstage against a black background. This would also be used as a practical for some ambient sound effects meant to come from the woods. Here’s the loudspeaker position markup from September:

At this stage in the process, the plan was to cover the pit, so we needed more loudspeakers for front fill because they’d be closer to the audience. We hadn’t figured out the center cluster yet; I had thought about VT4886s, but they would take far too much vertical space, so I was thinking something with one or more UPA-1Cs. The pair of CQ-2s we had for left/right mains covered most of the audience very well in the vertical plane, so we chose those with a little downfill loudspeaker on either side of the proscenium. If we used five of our sixteen VT4886s for front fill, we’d have several left for the US source, and we could tailor its vertical coverage very nicely.

In early October, when not many shows were in production, I reserved our black box theater for a day and invited the other sound folk to come listen to every loudspeaker in our inventory that wasn’t installed somewhere. We measured all of them, EQ’d them to be roughly the same on-axis, and then listened to the same set of diverse material through all of them, sometimes flipping between two side by side. This exercise informed our front fill and surround choices quite a bit.

Final Design

Front End

Some time passed, and the system design went through many iterations. How we ended up:

- Vocal front end – We had some wireless microphone receivers backstage, each of which had a high- and low-impedance output, so we routed the high-impedance outputs to a DM1000 to act as a listen station, and the low-impedance outputs to the Heritage. Vocal reverb came via a stereo aux on the Heritage with a couple of returns, and all of that got into D-Mitri via six subgroups, with exact routing changing on a cue-by-cue basis in the Heritage automation system

- Band front end – Some band microphones went into the Heritage, then the post-fade direct out of each went to D-Mitri. This gave an automation-safe control of the band to the operator upstream of D-Mitri. The prerecorded tracks came into inputs like the rest of the band, with additional outputs from QLab going to the aux injects for the drummer and MD monitors in the pit

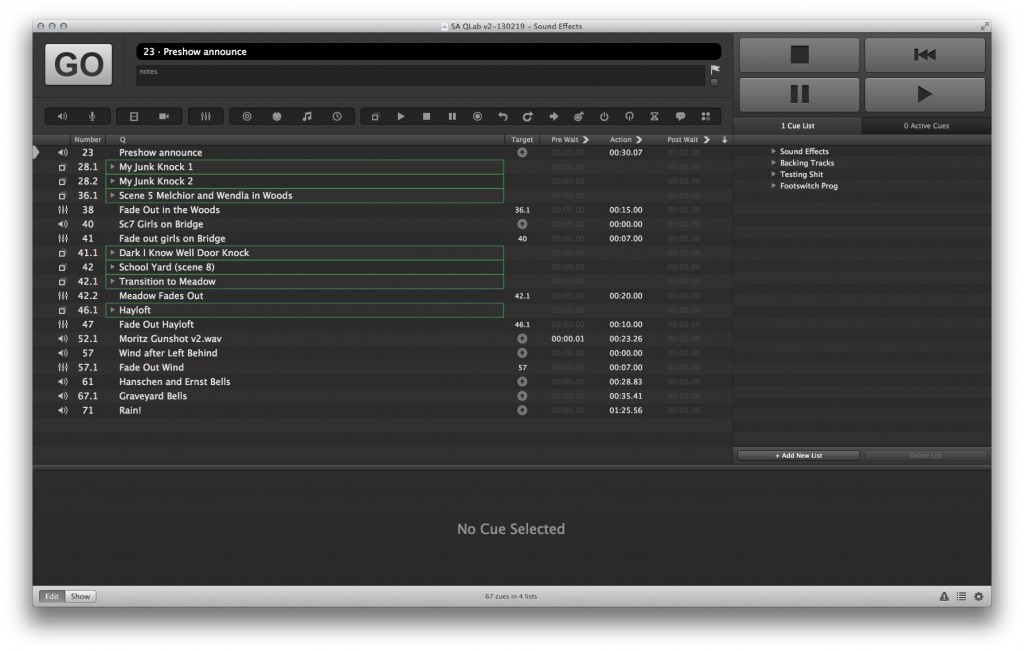

- SFX / utility front end – We ended up using QLab for playback since the QLab machine was there and it was reasonably simple. Pretty straightforward here, except that we needed to use the “B” inputs on the QLab playback channels for my computer in tech. We also had a QLab output that went to the lobby paging system to play the rain sound effect at the end of the show

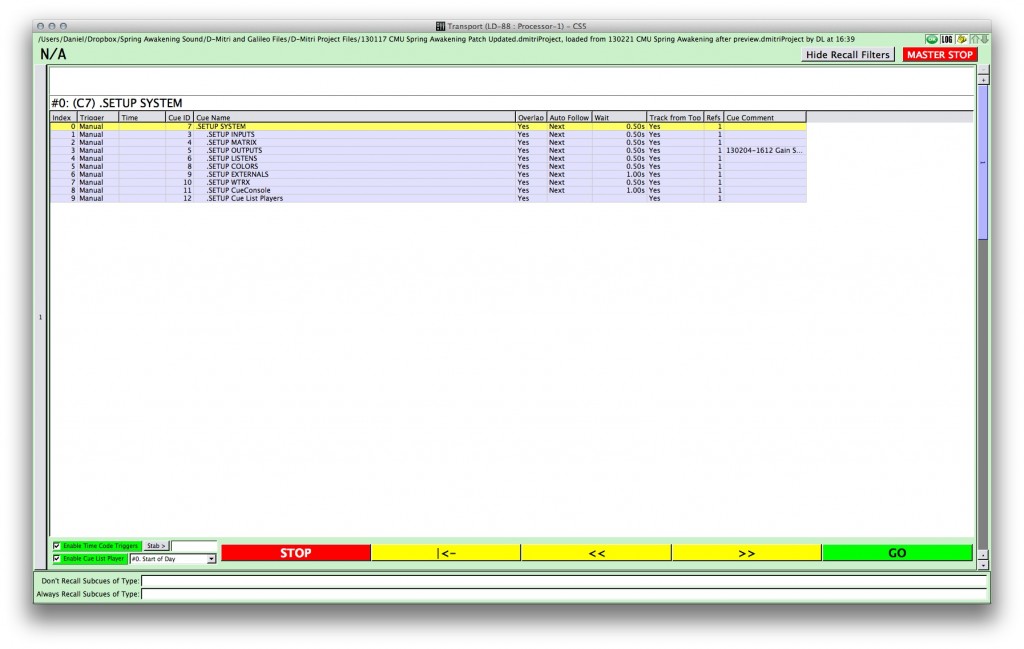

- Network / Control – We had initially discussed syncing lighting and sound for the gunshot effect in Act II, but decided that, given the lighting cue, it’d be just as effective to have the stage manager call it and have both ops trigger it manually. There was a substantial MIDI system to get the Heritage to control both QLab and D-Mitri, and to get the conductor’s button to trigger the backing tracks cue list in QLab.

- Loudspeaker Drive – Loudspeakers were driven either directly by D-Mitri or via the Galileo for systems that got the same signal but included several loudspeakers.

Loudspeakers

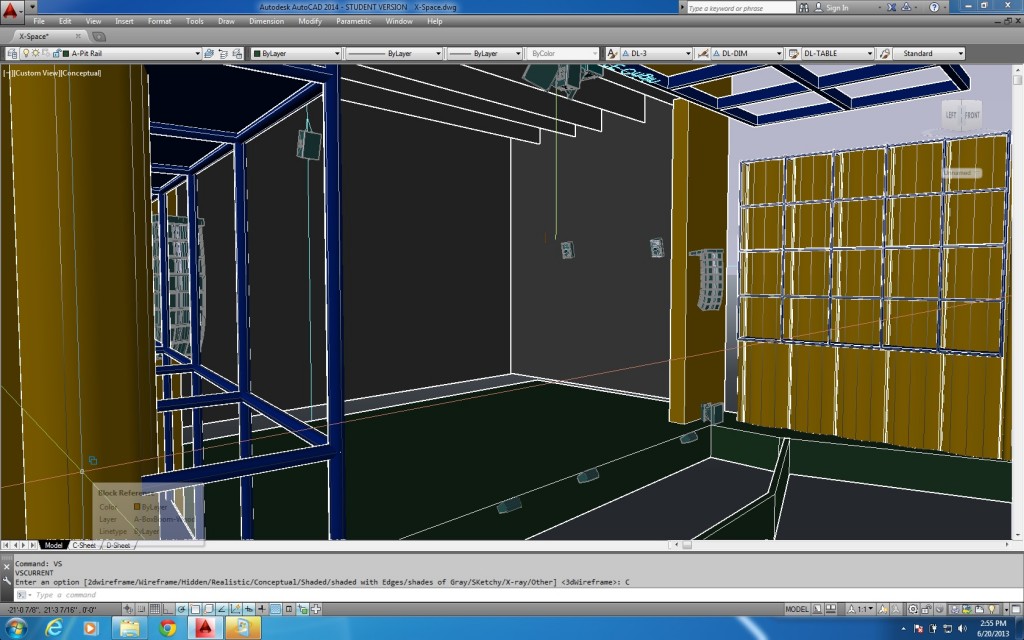

We pared the surround loudspeaker system down, and switched to eight VT4886s per side for mains. I chose the VerTecs because they’re a lot wider horizontally than are the CQ-2s, which was strange because we typically choose line arrays for the ability to precisely tailor vertical coverage, but here the vertical coverage of a CQ-2 and a fill loudspeaker was actually more consistent than the Vertecs’ and the horizontal coverage was inadequate. A Frazier CAT59 on the deck picked up where the arrays left off in front. The center cluster was a UPA-1C flanked by a pair of Frazier CAT59s to cover the lower area. Four JF60s lined the stage for vocals. A single CQ-2 upstage was our center band source. We initially planned to put the subwoofers (a pair of PSW-2s) on either side of the center cluster — the horizontal spacing would make them narrower, throwing farther into the room, and by flying them the vertical coverage would be more consistent.

Coordination and Load-In

Coordinating all the design elements was a bear of a job. The production used just about every lineset, and between the light strings and all the overstage electrics, it had more cable in the air than any other production we’ve done. Sound still got a lineset for our upstage source because it had been talked about since so early on in the process.

Early on in the process, we had also talked about using the box booms for loudspeaker placement early on in the process, but when the design changed to use the VerTecs this was no longer viable. Since the “flipper walls” that held the box booms were adjustable, we had to be very careful about their position so that the people in the boxes still had a clear line of sight to the arrays.

We worked with lighting to find space on the ladders on either side of the stage for foldback and on the FOH pipe for a surround fill loudspeaker.

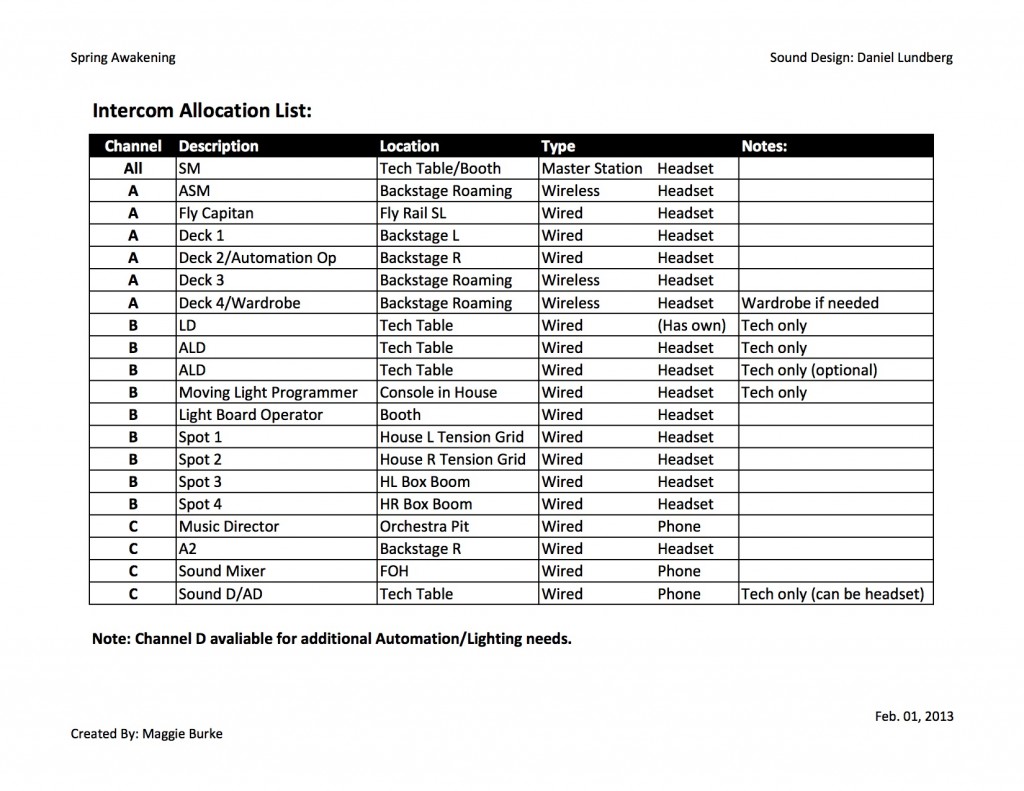

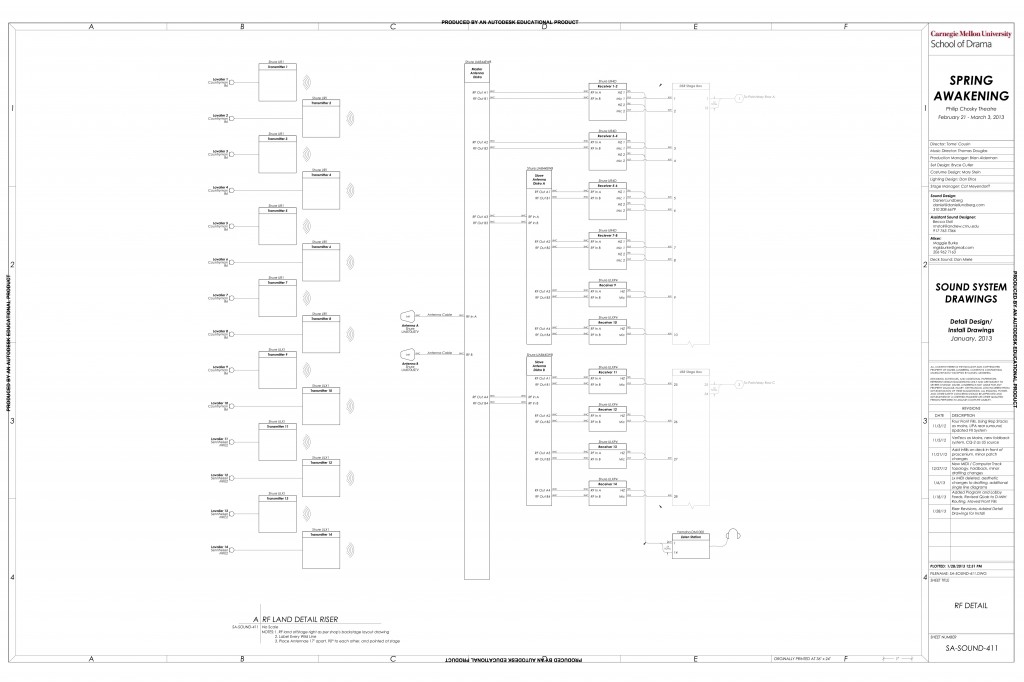

Intercom and RF needs for this show were pretty standard. We rented RF from two different places which complicated matters, but it worked out OK.

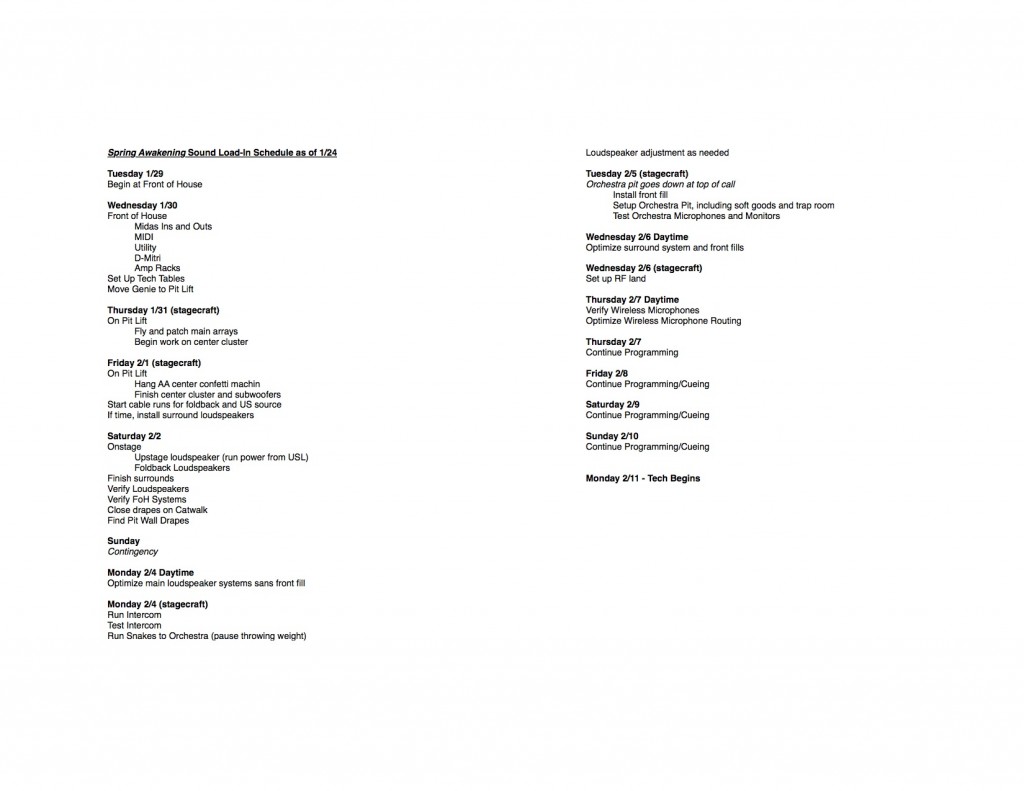

I did some additional detail drafting to clarify some of the complex bits for install. We concluded that most of the work with the patchbay at FOH would be faster to figure out once in the space, confident that the facilities existed. We documented these as we went with labels on cables and a rough Excel sheet.

Before We Began

I had done much of the basic D-Mitri programming, e.g., CueConsole and configuration stuff, by November. Since ours was the first show of the season to use the D-Mitri, we got proof of concept for our carrier tone idea in October, and we reconfigured the router and upgraded firmware before Spring Awakening officially had access to the space. The QLab file was well underway, and we’d spent a lot of time soldering new connectors on to our elements. I made some velcro doohickeys to attach microphones to the violin and viola. I also made wooden blocks the shapes and sizes of our two types of transmitters to give to costumes for fittings.

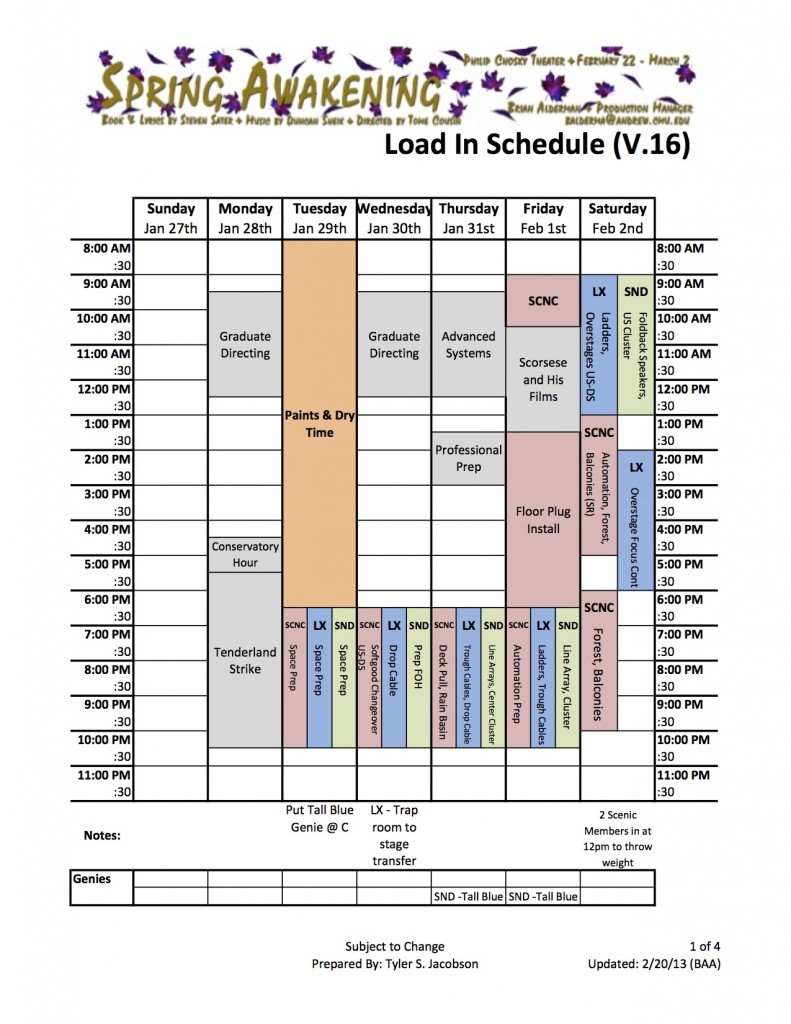

Schedule

All of the departments pushed the scope of show a bit, and the sound system was technically complex. We took care of front of house in the first eight hours of load-in with three of us working, put up the bulk of the loudspeaker system in the next eight, and continued with smaller tasks and in the second half of the load-in period. It was a slog, but our estimates were pretty close.

Results

Load-in went largely as planned. There some delays and reordering of tasks based on inter-departmental concerns, but any delay was easily contained in the contingency. I had to rethink powering for the MIDI Solutions stuff, so the MIDI patching changed some. We also ran into some challenges rigging the subwoofers as initially planned, so we talked with lighting and ended up putting them on the tension grid in a cardioid configuration.

Optimization, Tech, and Mixing

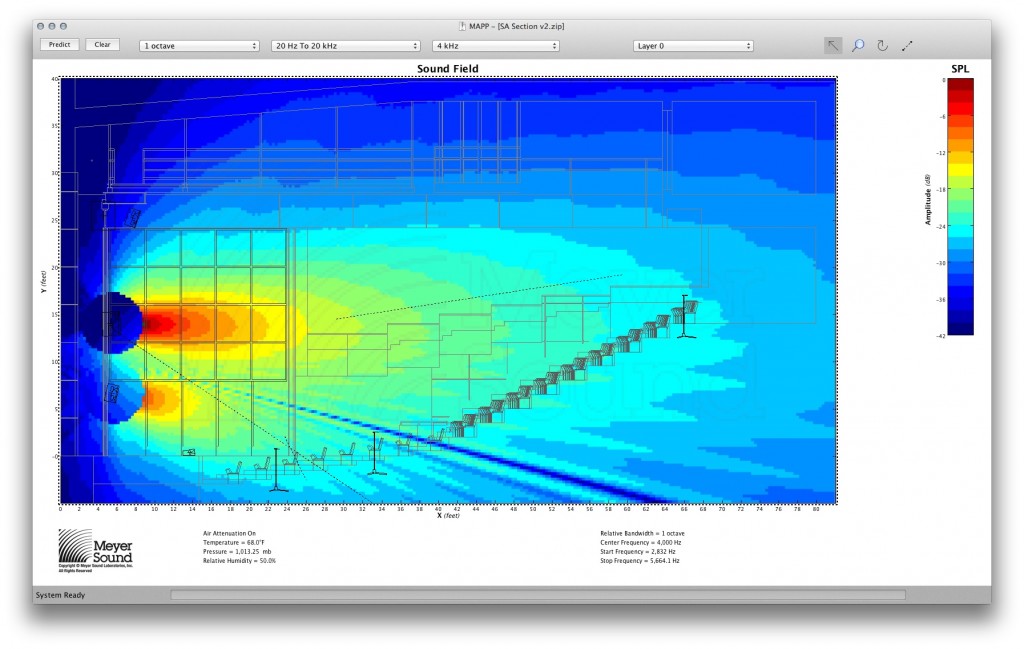

The optimization for this system was a little strange because we had to work in various pieces once installed, e.g., we tuned the main arrays and subwoofers before we had fills on the deck or all of the surrounds up. Some notes:

- Main system – We were satisfied with the original angles and trim height, but had to change the toe-in angle a few times before we were satisfied with consistency from side to side. The Fraziers on the deck were pretty easy to add in — we high-passed them pretty high, used all-pass filters to make their phase responses match the VerTecs, and set the level and delay so the transition point was about the third row side section.

- Surrounds – Our goal was to make the surrounds sound the same as the mains, which was pretty simple as far as EQ and gain setting went, especially since the surrounds would still use the main subwoofers (which were low-passed at 80 Hz). Aiming them was a bit trickier, since we couldn’t achieve front-to-back consistency with single boxes, and even if we could, we’d encounter some time delta problems when surround panning. As always, it was a matter of finding the best compromise, and ultimately surround effects “read” everywhere even if the levels varied ±5 dB.

- Vocal System – This was an ongoing battle. The UPA-1C is my favorite box in the inventory for listening to music on-axis, but predates the constant-Q horns to which we’ve become accustomed, so filling in the sides down front involved strange EQ on the Fraziers since some frequency ranges needed more filling than others. The Fraziers were too wide to be ideal for this fill job, but they were what we had. There was a hot spot in the back at center from the UPA-1C, so we adjusted the down-tilt angle several times. We ended up relying on front fill quite a bit for imaging and the first three rows, but the spacing on the front fill was apt and it worked out OK. We added some vocals to the mains during tech, which, while theoretically hair-raising because of the overlapping coverage, helped with intelligibility in the front sides and with imaging.

Programming

Tech

As often seems to happen on musicals, tech was largely uneventful for the sound department, . There was intercom and a Voice of God, and we got a decent amount of work done on vocal EQs and imaging. The sound effects had mostly been set ahead of time, so many were only played once or twice as we teched through the show.

Wandelprobe and Multitrack

The Wandelprobe was one of our biggest days. We had met all the band members during the band rehearsals earlier that week, and we helped them move into the pit. Everything had been line-checked ahead of time, and we soundchecked each instrument as musicians became ready, so there was very little time when all the musicians or cast had to wait. We started at the top of show. This was the first opportunity Maggie, the mixer, had to mix vocals without much interruption, so she had her hands full with that. I tried to get on top of gains on the Midas and levels in the D-Mitri during the first couple songs, and as we progressed I focused more on separating the instruments through EQ and routing. Thomas, the music director, played along with the prerecorded tracks with no trouble at all. We revisited a few songs. We recorded all of the wandel in WildTracks, so the next two days were spent setting the spatial panning of instruments, working with EQs to create separation in the mix, setting effects, etc. We finally put the show together in two dress rehearsals, refining vocal mixing and system optimization, band mixing, coordination with costumes, and everything else.

Lessons Learned

In retrospect, I would not change anything about the process for this show. Everybody got along well for most of the time, and the final product was pretty cohesive. The actors, musicians, and crew were all immensely talented, and the show was well received.

Sound-wise, if we had to do it again, we’d put the actors on earset microphones rather than forehead-mounted lavaliers, and we’d put the drums in an isobooth. Our biggest problem was a lack of dynamic range in all but the quietest numbers, because we had to mix up to the drums and were limited in gain-before-feedback by the actors’ microphone positions, so drums in an isobooth would’ve lowered the lower limit and earset mics would’ve raised the upper limit. I would have mic’d the toms individually; although I’ve been successful with ORTF overheads, snare, and kick in the studio, even for some rock and pop music, the overheads in the open pit had too much low-mid bleed from the PA, guitar amps, etc., to really be useful on the toms. I also would go with a different center cluster; although the UPA-1C is the best sounding loudspeaker we have when you’re on-axis, the not-constant-Q horn made a big high-mid hotspot in the back, and down in front and off to the sides there were frequencies at which the UPA-1C overlapped too much with the Fraziers and frequencies where they overlapped too little.

Thank Yous

The sound for this show couldn’t have happened without Maggie Burke, Rebecca Stoll, Dan Miele, Chris Evans, or Joe Pino, so thanks to them, and thanks to the rest of the team. I had a lot of fun and learned a lot on this production.